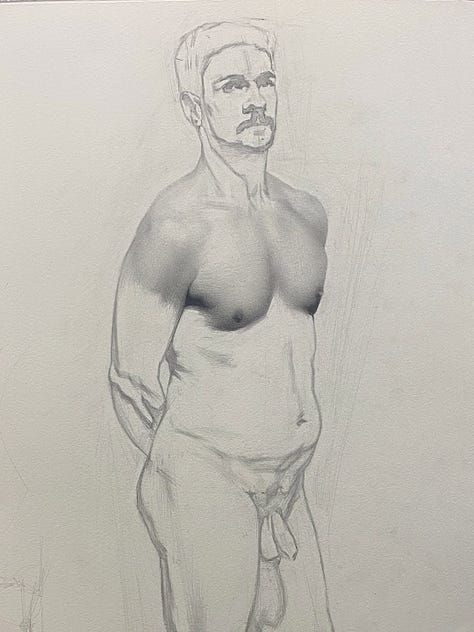

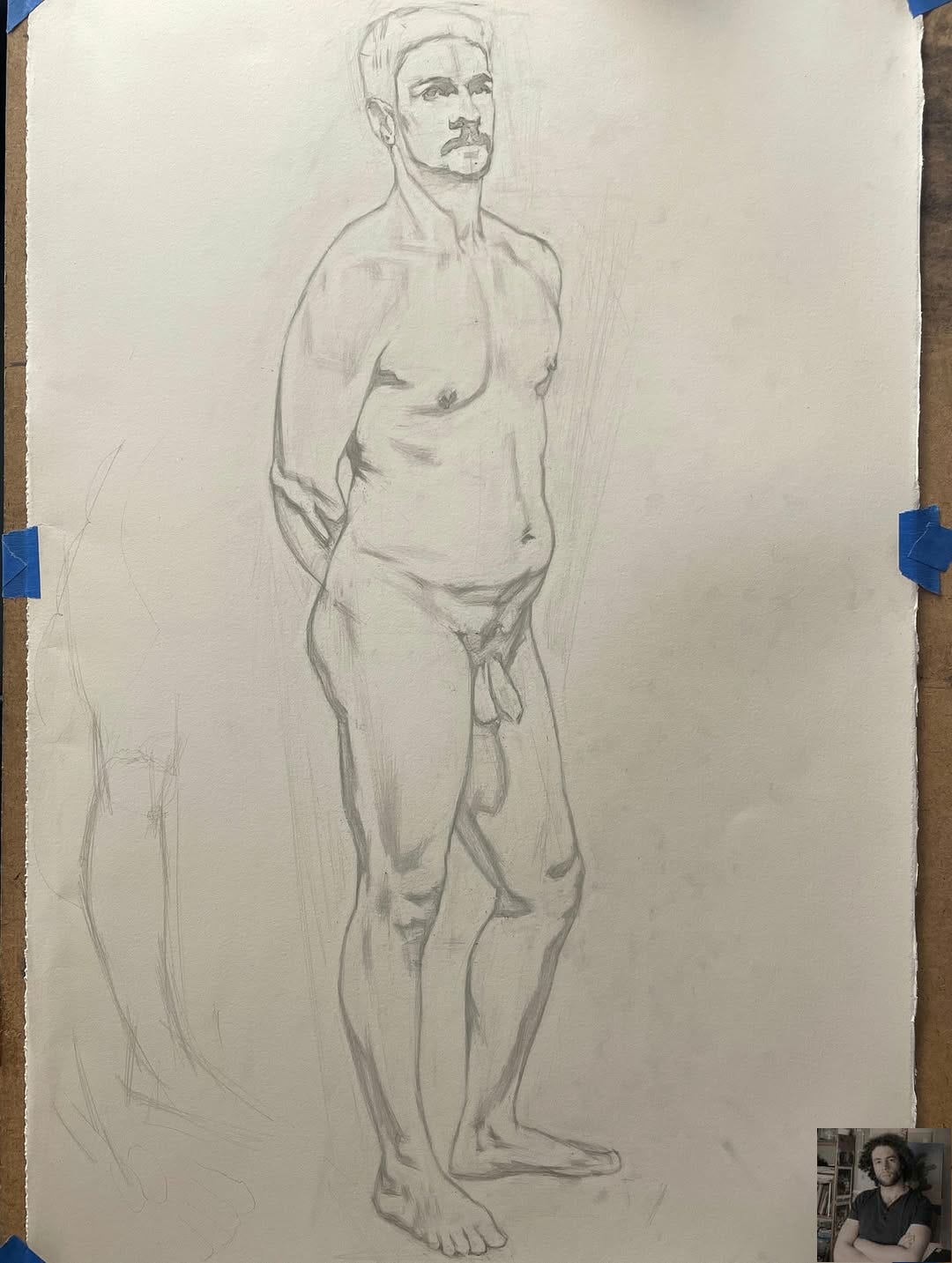

Long Pose Figure Drawing

~60 Hours

First of all, I hope you had a great Christmas, if possible, and that you’ll have an even better New Year.

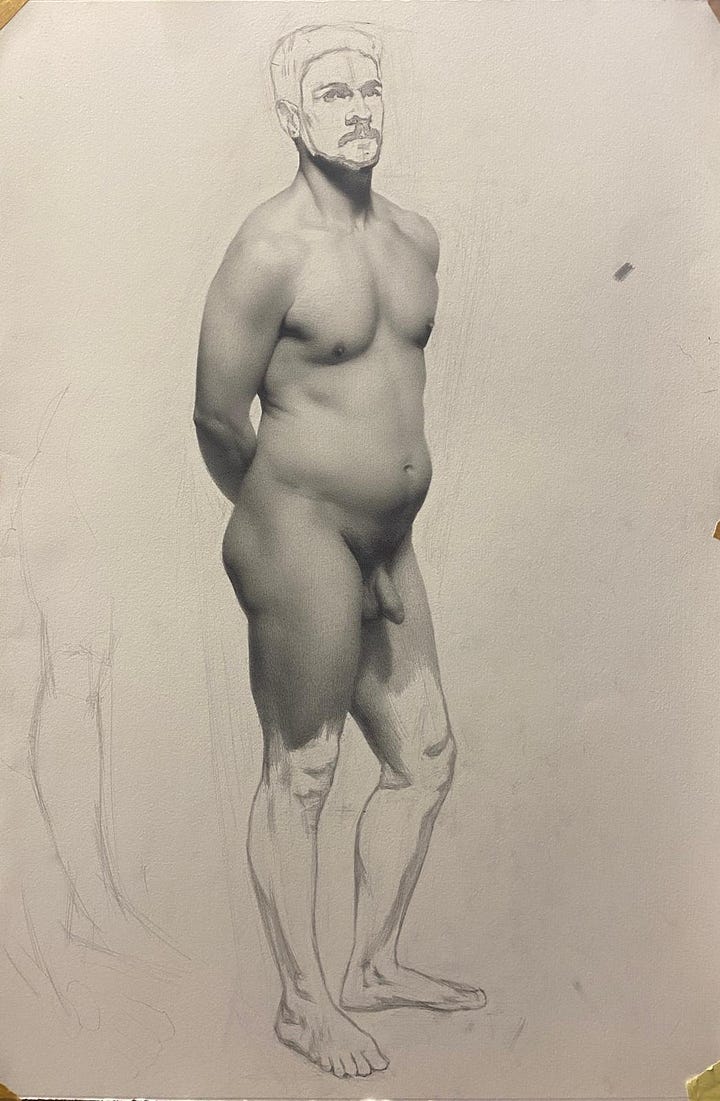

For this week’s topic, I decided to bring you one of my most recent atelier works: a long-pose figure drawing that I’ve been working on over the past three months, generally twice a week. The estimated working time is around 60 hours, give or take. There were sessions I couldn’t attend and others I probably forgot to log, so I’m rounding the number.

It may sound like a lot of time, but spread across these months, it flew by. And here we are.

The goal of this post is to share a bit of my experience and process, and to make some observations about it.

Part 1 — Explanation

Let’s go step by step, as we do in the studio with this type of drawing.

Drawing is a complex process. There are many things we need to pay attention to: proportions, structure, light and shadow shapes, hierarchies, and many other factors. It involves seeing abstract shapes and being purely visual, but also seeing things in a concrete and conceptual way. Knowing anatomy — and pretending you don’t know it — in order to achieve a true likeness of what you observe.

I know, it sounds strange. But you get the point.

With all these variables, how do you even begin?

If you’ve ever tried something like this, the answer is: by simplifying the process. We isolate these variables and study them individually until they become automatic. Then, when it’s time for the “final test,” we combine all these parts — like conscious juggling. And bam, a perfect drawing comes out.

Of course, this is an oversimplification, but pedagogically it’s a great approach.

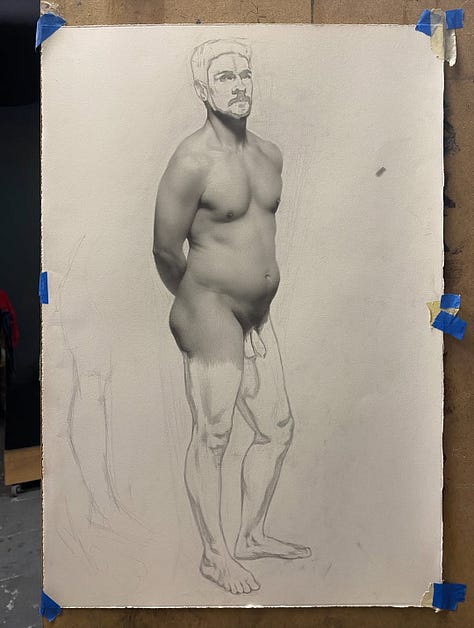

So first, we start with the block-in: the proportional map of light and shadow. This will be our puzzle, our mosaic, on top of which we’ll later model the form and create the illusion of three dimensions.

At this stage, we separate the drawing into light and shadow — this point is crucial, especially in atelier pedagogy. Since we’re simplifying the process, we want to reduce the number of uncomfortable variables as much as possible. That’s why we work with a single light source illuminating the model. This creates two clearly observable areas: light and shadow.

Our initial challenge is to draw these two areas — to build a mosaic or puzzle where the shadow shapes fit together with the light shapes.

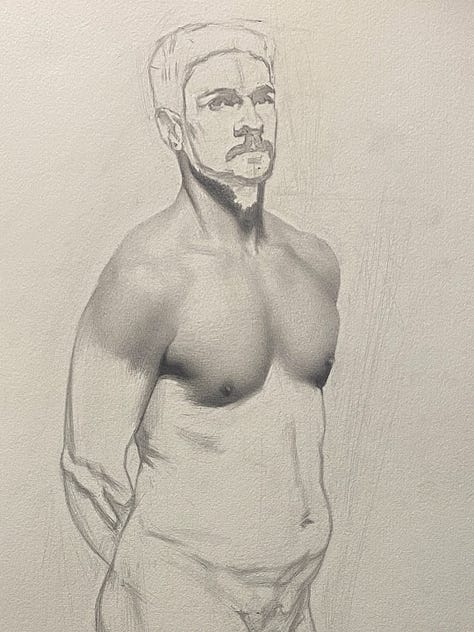

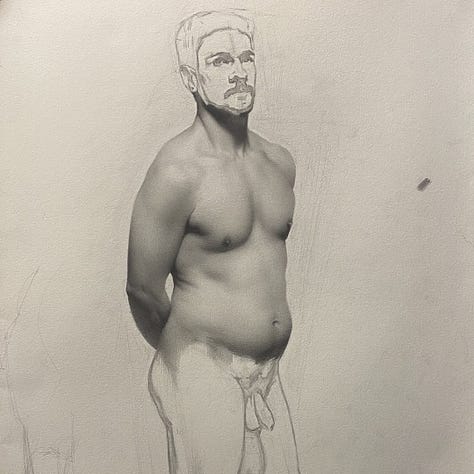

First 12 Hours

Within about twelve hours, I reached this stage.

To get here, I had to juggle several concepts. I took measurements to define a closed circuit and avoid falling into an infinite spiral of corrections. (Who hasn’t been there? You don’t define limits, start drawing one area, and shortly realize the drawing won’t even fit on the page.)

I thought from the general to the specific, from the largest elements to the smallest. I made sure the gesture of the figure was in place, that the leg cylinders were oriented correctly, before thinking about finer details.

I used straight lines and high points. Instead of trying to replicate curves directly, I used straight lines to represent the general direction. When a curve changes direction drastically, I intersect it with another straight line — creating a high point at that transition. A high point happens where there is a direction change.

Again, mosaic thinking: switching fully into two-dimensional mode and seeing everything as widths and heights. I’m no longer seeing a face, eyes, or a nose — I’m seeing abstract shapes and how they relate to one another.

Structure, in this case, means checking if symmetry is “turned on” in my internal software — if the structural points that support the figure, the skeleton, are properly aligned. Anatomy, on the other hand, comes in when abstraction isn’t enough, and I rely on conceptual knowledge to clarify doubts. More specifically: what exactly is happening at this point of the form? — that kind of question.

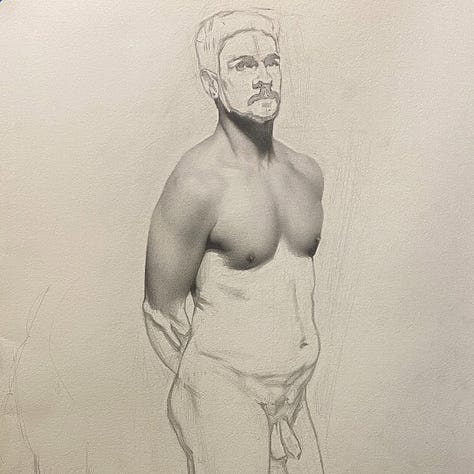

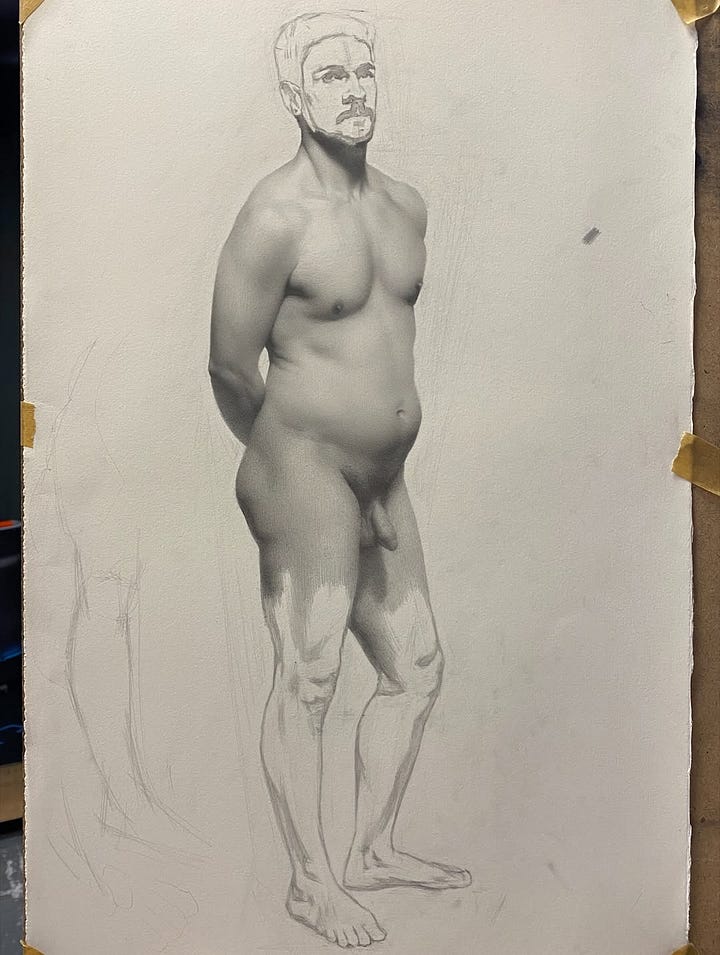

Modeling — The Cherry on Top

This is where modeling begins — the cherry on top of the cake.

Here we have two main families: the shadow family and the light family. These two families do not intermix.

In practice, this means that the lightest dark should always be darker than the darkest light — or, said another way, the darkest light should always be lighter than the lightest dark.

I approached modeling in two intertwined ways: a visual one and a conceptual one. For me, it’s difficult to separate the two.

Conceptually, I think of what I’m doing as if I were modeling clay. I try to feel the form. We’re now in a three-dimensional world. We divide the form into planes. With a single light source (at least in atelier work), the plane most perpendicular to the light receives the most light (not brighter than the highlight). Everything that turns away from the light becomes darker.

Another important concept is that the rotation is exponential when exiting the shadow family — most of the turning happens right at the edge of the shadow. That gradation is what creates the illusion of three dimensions. Is it a sharp edge, or a soft, rolling transition? We can also think entirely in planes if that helps. Or imagine being a tiny ant walking across the surface of the form.

This way of thinking not only reinforces volume, but also helps fight simultaneous contrast and optical illusions that often mislead us.

Visually, I look at the model and identify the lightest points. I half-close my eyes to see where they sit, and from that infer which planes are most perpendicular to the light. I also look for planes that are still in the light but almost escaping it — not shadow yet, but close.

I constantly compare the model to my drawing, checking if the gradations match, especially in the transition areas between light and shadow. I triangulate value relationships to make sure everything is aligned.

Hatching and Surface

Throughout the modeling stage, I always tried to apply a hatching that follows the overall morphology of the form. For example, if I think of the arm as a vertical cylinder, the hatching follows that vertical direction, only changing inclination where secondary forms modify the structure.

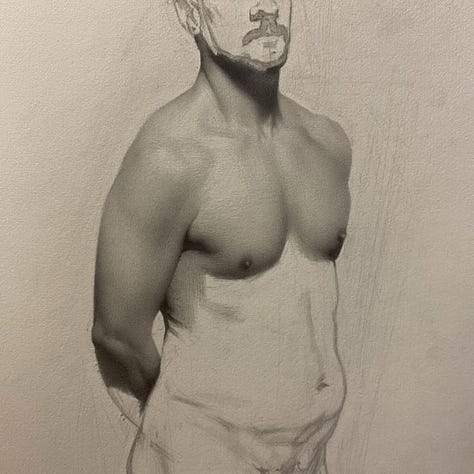

Final Thoughts

This drawing reinforced something I already believed: the block-in is where the magic happens — and you should never fully disconnect from it, even during modeling. Staying conscious of it at all times is crucial.

The block-in holds the pillars that will either support or collapse the modeling. In the next long pose, I want to be even more precise and clearer in my decisions — especially to improve the portrait.

And that’s basically it. There’s more, of course. A lot more that could be said.

This post came out later than planned because it went completely off track. I intended to focus on my experience, and suddenly I found myself explaining the entire process as if I were writing book chapters.

Let me know if you’d like me to dissect this method in parts with visual examples, or how you’d prefer to see it presented. In a way, writing this without showing everything feels like a mental organization exercise — which is great — but I’d love to know if you’d like to see this with clearer visual breakdowns.

Closing

Thank you for following my work. If you’d like to share it with friends, feel free — I appreciate every share and like to help this blog grow.

I’m still not entirely sure what this space is becoming. I’m discovering the path as I go. Strategically, it may not be the smartest approach, and it may even be naïve — but it brings me joy to see my work materialize and evolve. I hope it brings something useful to you as well.

This will be the last post of the year, so I wish you all a great New Year.

Cheers!

As someone who is dabbling in the same technique and learning it painfully, step by step, all I have to say is that your modeling work is a thunderous success!! You’ve captured the breathing, living softness of human skin on a flat sheet of paper. A true inspiration. May all of us who tread the same path arrive at such accomplishments! My highest praise!